“Our god’s name is Abraxas and he is God and Satan and he contains both the luminous and the dark world.” – Hermann Hesse, Demian

Carlos Santana: guitar, backing vocals

Gregg Rolie: lead vocals, keys, Hammond organ

David Brown: bass

Mike Shrieve: drums

Jose Areas: percussion, including timbales and congas

Michael Carabello: percussion, including congas

Alberto Gianquinto: piano on “Incident At Neshabur,” Rico Reyes: vocals and percussion, “Oye Como Va” and “El Nicoya”

Produced by Fred Catero with Carlos Santana

Author’s Note: This post corresponds to the Abraxas episode of Vinyl Monday, originally posted 10/14/2024. Save for audio/editing jokes that cannot be included in a text format, this is a faithful adaptation of the review chapter. To watch the full episode, scroll to the bottom of this post or visit my YouTube channel here.

The luminous and dark worlds colliding proved challenging at the turn of the 1970s. The Beatles were dunzo, replaced by Led Zeppelin as the biggest act in the world. Music was getting heavier: Black Sabbath scored a surprise hit with their sophomore album Paranoid. Genre was less gospel and more guideline. Jimi Hendrix broke up his experience for the more funk-oriented (and unfortunately-named) Band of Gypsys, then died before he could see the fruits of his labor bloom. Miles Davis would drop a fucking bomb on us all with fusion masterpiece Bitches Brew.

The pop scape was still ruled by folk. Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young scored one of the most preordered albums of the year with Deja Vu. Joni Mitchell was writing her career masterpiece Blue. But the flower power and influence of the once-vibrant San Fransisco scene was wilting. Jefferson Airplane went radical withVolunteers. Through excessive drugging, they’d effectively take themselves out of the race. Country Joe would never quite replicate the success he enjoyed surrounding Woodstock. Janis Joplin wouldn’t live to see 1971. A generational talent extinguished, her massive potential squandered. And the Grateful Dead just got way, way too big for the scene.

And then there was Santana.

If you presented their Cinderella story to a table of Hollywood producers, they’d throw it back to you and laugh you all the way to the cafeteria. It’s just too good to be true! In all of a year, this ragtag band’s namesake went from being a dishwasher in a restaurant to fronting one of the biggest groups to ever come out of San Fransisco. Bill Graham made major investments in the band's future, allowing them to headline his Fillmore West with no recorded material. Some may say he had too heavy a hand in their early years: he canned Chicago’s appearance at Woodstock and, as the story goes, wagered his boys in a coin flip with It’s A Beautiful Day to see who would get to take the stage. Whichever they were, heads or tails, Santana came out on top. With a kid drummer and a bandleader tripping sacks, they went from nobodies to superstars overnight.

By the time Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock film was released in spring of 1970, Santana finally had their debut album out. About that initial success, Carlos said: “It felt like we went from high school aspirations, pretending we could play with Wes Montgomery to Gabor Szabo to BB King, to all of a sudden being in the arena with these people. But instead of having your feet planted in the ground, you were hanging by your feet and somebody’s twirling you around as fast as they can twirl you.”

(quoted from: “Santana – Abraxas: Carlos Santana, Greg Rollie, Michael Shrieve” In The Studio with Redbeard, 10/11/2020)

With a genre-busting, wildly inspired sophomore album and controversial art, Santana were about to piss all the purists and puritanical pearl-clutchers right off.

Firstly, about that art. It’s a damn shame the YouTube gods would never let me show it off in all its glory! Abraxas has one of the most beautiful covers in my whole collection. (But you know me and art as album art.)

Pictured: Mati Klarwein, Annunciation (1961)

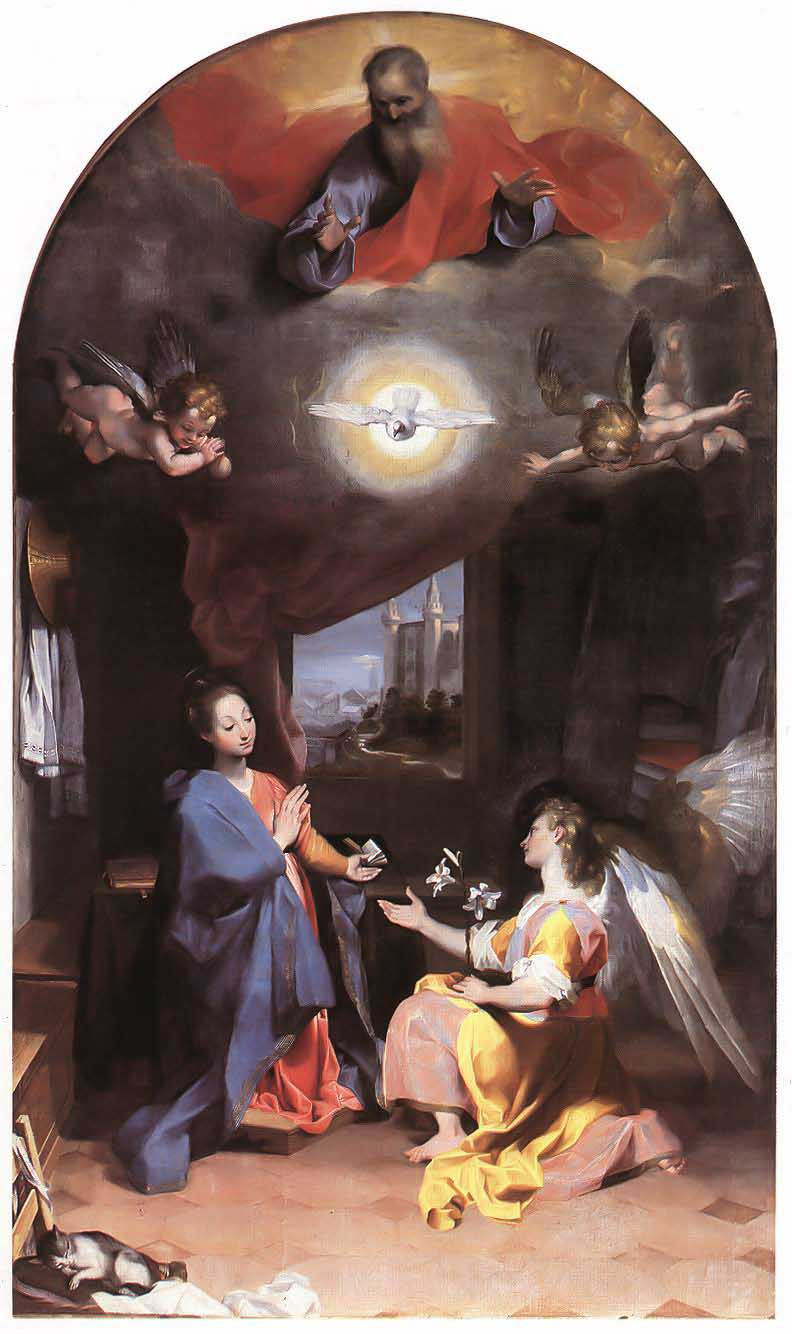

Mati Klarwein’s Annunciation is radical and challenging. It’s nude. It’s Black. It’s blasphemous. Angel Gabriel is big-breasted and bright red with wings and tribal tattoos. It slams so many cultures together: a Christian story, Hebrew characters, African dancers, an Indian elephant. (And, of course, the artist; stoned and grinning with watermelon in hand.) For reference: here are some examples of how the Annunciation scene is historically represented in Western art.

Pictured: Fra Angelico, Annunciation (tempera on panel, c. 1426)

pictured: workshop of Robert Campin, Annunciation Triptych (oil on oak, c. 1427-1432)

pictured: Leonardo da Vinci, Annunciation (oil and tempera on poplar, c. 1472-1476)

pictured: Frederico Barocci, Annunciation (oil on canvas, 1582-1584)

Very...demure.

I imagine when Carlos saw a print of Klarwein's Annunciation in a magazine, he recognized this radical yet universal quality in Santana’s music.

Through my college years, Abraxas was never off my turntable for long. My dad and I went to the record store together, I picked this one out because I loved the art. He bought it for me because he felt I should have it.

He was right. At the time Abraxas came into my life, there was nothing like it in my collection. I didn’t have much jazz. I didn’t own any other Latin albums (an infuriatingly reductive umbrella term. There’s so much within it: mambo, salsa, cha-cha-cha, merengue, Santana was even inspired by Santeria.) My recordcollection at the time was almost exclusively psych rock, hard rock, and blues rock. In that sense, my experience discovering Abraxas wasn’t unlike a listener discovering it in 1970.

Felix Contreras for NPR said: “Among the many monumental records released in the late 60s and early 70s, Santana’s Abraxas stands tall not only for its musical innovation and vision, but also because, after all, it still sounds so damn good.”

quoted from: “50 Years Later, Santana’s Abraxas Still Changes The Game” Alt. Latino via NPR, 9/25/2020

Why has Abraxas held up?

Of course, part of it is Carlos’s playing style. It was singular in its time. When he emerged in the mainstream, no one in rock-and-roll played like this. No one played with this much open space between notes. He absolutely lifted that from Gabor Szabo; he’d stretch notes out beyond the horizon.

Carlos’s phrasing is very deliberate, maybe the most methodical of any guitarist we’ve studied on this series. When they met for the first time, Jimi Hendrix told Carlos: “I like your notes.” Carlos plays quite soft here. He isn’t cranking the volume like Zeppelin or Sabbath were in 1970. I had to strain to hear some stuff, like the gentle strums on “Black Magic Woman.” Both are a Gabor thing as well as a Peter Green thing – listen to the stuff Peter did with John Mayall.

But Santana’s secret weapon? The absolute calamity of drums. Many Carlos copycats have emerged in the subsequent decades, but the drums remain unique to Santana. It’s a challenge to make three drummers work; the Allman Brothers struggled with two at times. But with some careful motions, they did. The secret? Joseand Michael played straight Latin stuff, while Mike played straight jazz so he’d stay out of the other guys’s way. This album is just packed to the brim with percussion: shakers, maracas, cowbells, wood blocks.

Abraxas’s atmosphere remains singular. Other albums I’ve evaluated have a similar haunting, space-between quality. See The Doors’s self-titled or even Gabor Szabo’s Dreams. All 3 albums tap into a similar energy, but only this one transmutes it this way.

With a dissonant swath on piano strings, Singing Winds Crying Beasts reveal themselves to us. This composition is credited to Michael Carabello. The “singing winds” are the bells and cymbals, the “crying beasts” are Carlos’s guitar. Not many songs I’ve encountered have this quality about them. Lots of introductions invite you into the record, but very few draw you in without having to reach out. Back in the Doors episode, I talked about the veil between here and what’s beyond us. I love this time of year because it feels thinner. It feels thinner on “Singing Winds” too. It’s like riding on a river boat into a thick forest as it comes alive at twilight. Parting gauzy cobwebs of sound. The nymphs won’t reveal themselves to you just yet, but keyboard and conga creatures peek their heads out from the greens

In one of my favorite moments on the record, we segue into Santana’s interpretation of Black Magic Woman. Instead of Peter Green and Fleetwood Mac’s gentle blues shuffle, Santana leads in with Gregg Rolie’s organ; shifting its weight on its feet. About that first appearance of the BGM motif, Vernon Reid said: “the guitar seemed like a voice.” (quoted from: “50 Years Later, Santana’s Abraxas Still Changes The Game” Alt. Latino via NPR, 9/25/2020)

Let’s take a moment to compare and contrast with another rock record – one largely forgotten by rock critics of today – from 1970: Mountain Climbing. With The Great Fatsby himself, one of the great underrated guitarists (and one of my more...confusing...fave raves,) Leslie West. Les said something like he wanted his solos to be "singable." Though Carlos was doing a totally different thing stylistically, tonally – note his subtle rhythm playing and flourishes peppering the verses – both these guys had a very vocal quality about their lead playing. That’s really cool to me.

Fleetwood Mac’s and Santana’s “Black Magic Woman” really aren’t that different from one another. Instead of completely rearranging the whole thing, Santana took the original and elevated it. They brought a whole new feel. They made it a mambo. This track establishes all of Santana’s strengths in one fell swoop: David’s dynamic bass, Gregg’s understated but pleasant voice. The way Mike straddles the very bottom layer and very top layer of sound with his subdued drumming and occasional favor of the cymbal. It's in Michael and Jose’s textures and chemistry, and all these guys’s chemistry with each other.

You don’t get this from everyone playing their parts separately. You get it from bodies in a room.

“Black Magic Woman” progresses effortlessly and naturally until cresting into their tribute to Gabor Szabo. Ah yes, the also unfortunately-named Gypsy Queen. This is quite different from the original I remember. The guys inject energy into it. Anticipation. I think it comes from picking up the time and Mike stepping into the spotlight with his fellow drummers.

You may laugh at people who don’t know “Black Magic Woman” was a cover. I give them grace. I didn’t know “Oye Como Va” was a cover.

Like “Black Magic Woman,” Santana took the core of Tito Puente’s cha-cha-cha and made it bloom. Mike lays down a steady swing, while David plays the best bassline on the record with little variation. It’shonestly more of a showcase for Jose, Michael, and Gregg than it is for Carlos! They swap around lead linesand rhythm motifs and hand the song off to each other with ease. If you don’t at the very least shimmy your shoulders, something is wrong with you. You can always tell when a group had a blast in the studio. “Oye Como Va” just has a great vibe and bubbling energy. It’s very communal, right down to the group vocal.

Rounding out the first side of the album is Incident At Neshabur, a collab between Carlos and guest pianist Alberto Gianquinto. This is the most overlooked instrumental track on the album! It’s not prog, but it’s progressive. We’re heavy on the Latin feel for the first few bars, stumbling around in dizzying chaos, before breaking into 6/8 time (inspired by Santeria music.) If anything were the midpoint between Santana’s self-titled and Abraxas, it’d be this central motif. It’s like the sophisticated older sibling of “Soul Sacrifice.”

I love the conversation between guitar and piano, how they guide the song through all these changes. Especially when the song tumbles down the hill from Carlos’s solo and back to the 6/8 ostinato. The energy is electric. Then the song simmers down into an absolutely beguiling exercise in Carlos’s extended feedback notes. It just opens your chest right up after not knowing you’ve been holding your breath for two minutes. Alberto and Greg get to converse some, with Gregg settling into rhythm and Al playing a gorgeous solo over top.

Opening side 2 is Se A Cabo, credited to Jose. It’s a great little tune, absolutely killer African rhythm-infused moment for all 3 of our drummers and our Hammond organ. I don’t totally hate the panning on Mike’s little drum break. It accentuates the fluid motion he’s finally broken into. I’m just wondering why a song called “it is finished” is a side leader. I don’t want to jump to conclusions but this seems like a case of poor sequencing, or maybe the limitations of the vinyl format. There’s only so much space on one side of an LP, 25 minutes max. Now that I think of it, the whole 2nd half of Abraxas is arranged funny. I wouldn’t have put any of these songs in this order!

Next is Mother’s Daughter, a Gregg original. Of the songs with lyrics, I feel this is the weakest. It’s a pretty generic narrative of “show mean mistreating woman who’s really the boss!” Sonically, it reads as a regression to the first album. Though I appreciate the opportunity to put a little edge into Carlos’s playing. He’s been super light and airy, he’s been earthy, he’s been liquid smooth. For a moment on “Mother’s Daughter,” he captured Jimi Hendrix’s fire

After the most rock-oriented track so far, we snap back to the Latin influence with Samba Pa Ti. The romance of the eden we’ve stumbled into, the tragedy of man.

It’s a bolero; a favorite of guitarists in the late ’60s. Very romantic. “Samba for you.” One might even call it sexy. But after learning the story of how this song came to be all I can hear is the anguish.

The concept for “Samba Pa Ti” came to Carlos upon returning home from Santana’s first European tour. Hewas still hurting from the jet lag and opened the window for some fresh air. Poor guy forgot he was in New York City. There’s no fresh air to be found there. On the street below him was a drunk man, with a bottle in one fist and his saxophone in the other. He was struggling with which to put in his mouth; his instrument or the booze. This internal struggle inspired Carlos.

“...all of us (can) be out of San Quentin and still be prisoners by our own habits.”

quoted from: “Santana – Abraxas: Carlos Santana, Greg Rollie, Michael Shrieve” (In The Studio with Redbeard, 10/11/2020)

Not unlike A Love Supreme’s “Psalm,” Carlos came up with words to play instead of sing: “To every step, in life you find, freedom comes from within. If you can understand, and woman, you should love your man…” He wrote it, arranged it with Greg, and Jose named it. Samba pa ti. “Samba for you.”

Hendrix could make his guitar go to war and drop bombs, Carlos could make his guitar cry and dance in the street as it sings to us. It’s lyrical, reaching to the sky before curling inwards again. The chords Gregg plays underneath are just gorgeous. It’s cliché to call organ a “mourning” instrument, but it is here. “Samba” is a devastatingly human moment on such an ethereal record. The sun comes out with the bass, bouncing drums, and very subtle rhythm guitar. Through Carlos’s phrasing we go from sorrow to self-pity to joy. But just as soon as it comes, the optimism fades away as the song fades out.

If “Oye Como Va” was all the way on the Latin end of the latin rock spectrum, Hope You’re Feeling Better is all the way on the rock side. Greg contributed the most rock-oriented numbers. This is the most underrated lyrical number. It’s so cool because it’s like something Deep Purple would’ve done! It’s heavy and organ-driven in the same way, with motion in the undertow thanks to Dave’s sparse bass. It shows off the edgier side of Carlos’s playing style too. He had incredible flexibility as a player. Not to say Abraxas is passive, but we haven’t heard this bossiness yet and we won’t hear it after. Greg hasn’t performed like this either, he’s adopted a snarl.

Abraxas as a whole isn’t passive. It’s intricate and careful. You have to be careful to execute that intricacy. And the energy is a lot lighter. “Hope You’re Feeling Better” is darker, less detailed. It’s big blocks of color as opposed to the fine-tuned scrolls.

And finally, El Nicoya. The fact this album ends with “come on, Chepito!” Basically telling Jose to hurry his ass up! Is so funny to me. Sonically, as we journey out of the black night and into morning, we catch a glimpse of a fire up the mountain. It’s a ritual dance. We don’t get to be part of it, we just observe for a moment before venturing back to reality.

If we’re talking all the way across the Santana canon, his best would have to be Love Devotion Surrender with John McLaughlin of the Mahavishnu Orchestra. But as far as Santana the band? This is probably the best.

Carlos said it himself, Abraxas lingers.

“I think about planting certain sounds, certain cries...certain things in (the audience’s) hearts...2 months after you leave them, they say, ‘Man, you guys left me pregnant with this sound.’” Immaculate conception. “A lot of bands, as soon as they unplug the amplifiers, it’s all over. So there’s something else that’s beyond "Black Magic Woman" or "A Love Supreme" or whatever it is. Ultimately, it’s what you put inside of it that makes it more than a song.”

quoted from: “Santana – Abraxas: Carlos Santana, Greg Rollie, Michael Shrieve” In The Studio with Redbeard, 10/11/2020

Someone, I don’t know if it was Mike Shrieve or Vernon Reid, likened Abraxas to twilight. Considering the Hesse quote at the beginning of this review, that’s synchronicity if I’ve ever seen it. Even more so, considering synchronicity comes from Jung and (I think?) he spoke of "abraxas" too.

From the packaging right down to the playing, Abraxas is gorgeous. It’s one of those moments us mortals will never totally grasp. It’s the space between. We’ll always be reaching out for it, wanting to grasp it and never quite touching it. But sometimes, it reaches back. And welcomes us into the warmth, the comforting darkness. It’s mysterious. This album is so many things at once: rock, blues, jazz, Latin. And so many things within the “Latin” umbrella. Even a Hungarian jazz guitarist’s influence makes its way into the mix! Abraxas is one of the most inspired albums of the 1970s. So what it’s not “authentic.” Who gives a shit? It honors tradition. While smashing it to bits. While creating a new one. Santana did something really beautiful with this record: they painted rock-and-roll in their image. Their respective heritages as men, and their collective heritage as men of the church of rock-and-roll.

Yes, there’s something spiritual about this album. The music created in the collisions a treasure to covet for all time. Some may try, but it’s too ephemeral to imitate. Abraxas truly is both the luminous and dark world.

Personal favorites: “Singing Winds Crying Beasts,” “Black Magic Woman,” “Oye Como Va,” “Incident at Neshabur,” “Hope You’re Feeling Better”

– AD ☆

Watch the full episode above!

Comments